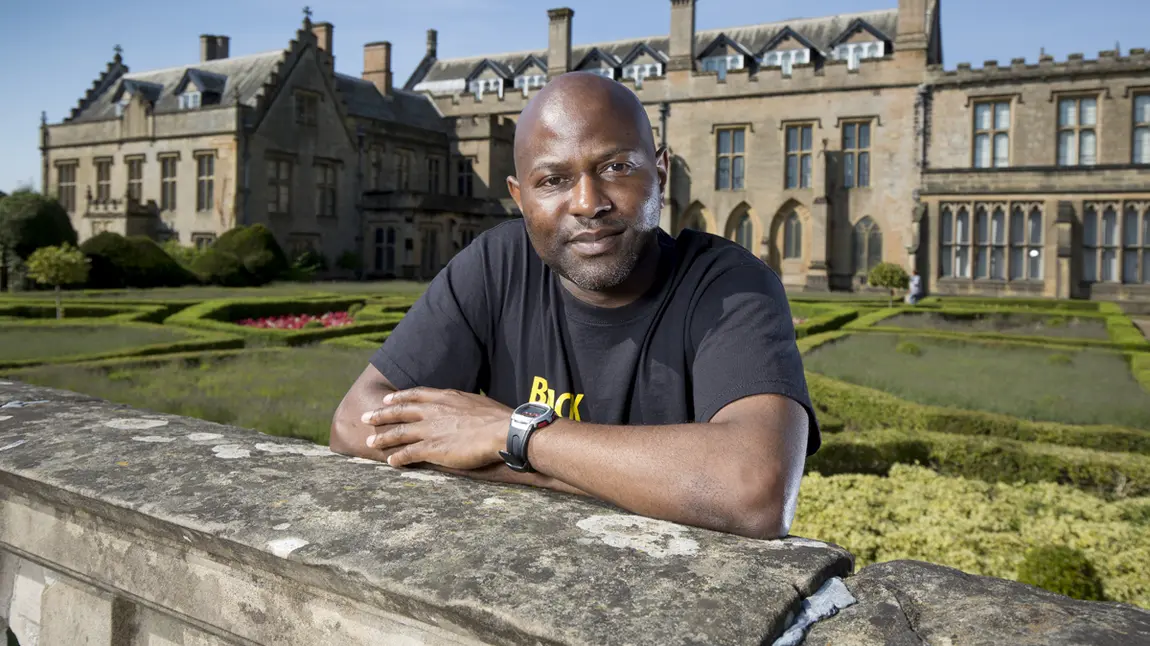

Changing lives: Unearthing slave histories gives Clive a better outlook on life

Clive Henry was among a group of volunteers who brought the often hidden links between heritage sites and African slaves into sharp focus through the Slave Trade Legacies project.

The Nottingham taxi driver, who spends much of his spare time campaigning against racism and injustice, joined the HLF-supported group while he was at his lowest ebb in life.

"Whether we are black or white, we are all connected as part of the same human family."

-Clive

He was exhausted after representing himself in a race discrimination case against a previous employer which reached the European courts.

“It was a very painful time, I had to dig deep to survive,” says Clive.

“The project gave me a new focus and helped me to heal by getting out and about and meeting people. It showed me how my pain was nothing compared to what my ancestors had been through and it made me go further and find out about how the human race started in East Africa and migrated across the planet.

"Whether we are black or white, we are all connected as part of the same human family.”

A message from Mandela

The father-of-three went on to become a passionate anti-racism campaigner, particularly through social media. Brought up in Nottingham by Jamaican migrant parents who encouraged him to read and expand his knowledge, he puts his self-reliance down to becoming the man of the house at the age of just 11 when his father died.

A spur of encouragement in more recent times came from Nelson Mandela, who was then retired from public life but told Clive to “keep going” in a message sent from his office.

The self-starter, now 43, did just that and joined the Legacies project which, thanks to National Lottery players, was set up in 2014 by Bright Ideas, a social enterprise in Nottingham.

“Mandela spent 27 years in prison and it put what I was going through into perspective,” he said. “That one comment took me to the next level because I was at my lowest ebb. I began to build my life back up and started a social media campaign. The Legacies project cemented that.”

The history of slavery

Clive joined around 40 volunteers who were largely of African-Caribbean heritage and from urban Nottingham. They carried out research, organised events such as talks and film screenings, and visited attractions across the country, including Newstead Abbey, Lord Byron’s stately home in Nottinghamshire which the poet sold in 1818.

The buyer was Thomas Wildman, whose inherited fortune derived from his family’s ownership of one of the largest sugar plantations in Jamaica. The Quebec Estate plantation, which made Wildman’s purchase of Newstead Abbey possible, had been served by more than 800 slaves.

One sombre moment during the project’s research phase came on a trip to Hull Museums’ slavery collection when the volunteers lifted up iron chains which once shackled the traders’ human cargo.

“By holding the chains you’re reliving what your ancestors went through,” Clive said. “You can watch movies about slavery or read about it in books but it makes you realise that they went through hell.

“I try to turn negatives into positives and what I took from it is how strong that generation was to endure physical and mental torture with no hope for change.

"Their DNA is running through our veins so we should make the most of the education and the opportunities we have now.”

Emotional times

The difficult forays into the past – and the long bus trips to venues in Bristol, Liverpool and other places - led to the participants forging strong bonds with each other and most found the project to be cathartic.

They named themselves the 'Slave Trade Legacies Family', united through the stories of pain and misery as they tried to return a missing chapter to the attractions.

“There were emotional times when we saw the realities of what had happened in the past,” Clive said. “But we worked on a number of different projects together, had meetings together and ate together. We were all on the same journey.” The ‘family’ was able to speak with one voice in sharing its reflections with institutions such as the National Trust and English Heritage.

Clive became one of the group’s spokespeople, appearing in short films which continue to be used in academic and community forums. At Derwent Valley Mills, a World Heritage Site in Derbyshire, they ensured that an exhibition included the fact that cotton picked by slaves was used at the factory.

Changing minds through education

One of the volunteers’ biggest achievements was creating Nottingham’s first black history society after the Legacies project ended last year. Clive is also involved in the Black Lives Matter social justice campaign and has become an advocate of using education to fight injustice.

“The project has shown me that education can change people,” he said. “History in schools is like looking through a keyhole, it takes out the equation that a part of Britain’s wealth was built by slaves.

"The older generation never learnt it and because it’s painful, they don’t want to find out and pass it on to their kids. I just want to educate people and expose truths. I also want to show that black people’s history didn’t just start with slavery. If we can teach the next generation to see people of all colours as human and there will be less racism and discrimination.”