Four artists on how heritage has inspired them

Luminary by Heinrich & Palmer

Crossness Pumping Station, London

How did the heritage of Crossness inspire you?

Anna Heinrich: The moment we saw it, we thought: wow, we’ve just got to work with this space. We did quite a lot of background research – how it functioned, the shipping that went alongside it.

However there's already so much information already at Crossness about how the building operated and the history of the sewers.

We wanted to create something quite immersive that could be experienced on a visceral level.

Can you describe your artwork?

We're treating the whole place like a massive light installation. There will also be a large-scale video projection onto a voile screen which will hang from the first floor to the ground floor.

We’ve been taking recordings of the engines running and sounds around the building and have used those samples to create a soundscape.

What do you think heritage can bring to art?

You can use art to reinterpet or reveal hidden stories, sometimes quite uncomfortable stories. It shines a different light on the heritage.

- Luminary was commissioned by Peabody and Crossness Engines Trust. It takes place from 12-14 July 2019. Find out more on the Thames Meadow website and book tickets on Eventbrite.

- Read more about our support for Crossness Pumping Station.

Ship by Anna Gillespie

Half Moon Bay, Lancashire

How did the heritage of the area inspire you?

Anna Gillespie: I was particularly attracted to all the images I saw online of the old fishing boats, and the way people used to fish the bay.

I came up with the idea for a ship: it’s almost like two prows, with a character on each end.

I wanted it to represent both looking back to the past but also looking to the future.

It also represents this incredible mix of Viking and early Christian heritage, all very much going on at the same time.

How does it fit into the landscape?

The sculpture ended up in Half Moon Bay. You can see the nuclear power plant, the port that takes the ferries out to the Isle of Man, there’s a lot of dog walking, a very good greasy spoon café.

People seem delighted that this sculpture has been given to them, it feels like somebody’s valued that community.

How did you make it?

The boat structure is made out of corten steel, which naturally rusts. The figures are made out of bronze. In the centre there is a block of local Longridge stone.

The whole thing is conceived as though it’s hollow… you can stand there and look through the sculpture of a ship, you see these modern ferries going in and out through the Heysham port.

It is very much referring to the heritage, but it’s also saying: this sense of coming and going, of seafaring, of looking out to sea, is still very much alive.

- Anna was commissioned by Morecambe Bay Partnership's Headlands to Headspace project, supported by The National Lottery Heritage Fund.

- Find out more on Anna's website

Stolen Things by Paul Rooney

Courthouse Museum, Ripon

What inspired the Stolen Things sound installation?

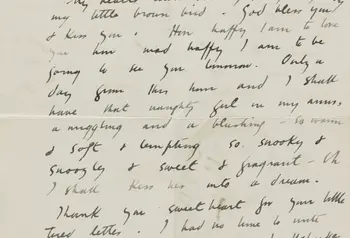

Paul Rooney: I went through newspaper archives looking for reports of trials involving children as the accused, and decided to focus on 14-year-old Ann Lupton’s group of child shoplifters.

I wanted to contrast the severity of the law, represented by the courtroom, with a vulnerable child’s interior emotions.

How did you create her "voice"?

I found a York Herald court report of her trial in 1853. But the report does not describe any of her words or actions, so I imagined what she might have been thinking, or daydreaming, during the trial.

I also used the Victorian children’s hymn Do No Sinful Action, the Taylor Swift song I Did Something Bad, the writing of Jean Genet and even the recent Japanese film Shoplifters.

What effect did the physical courtroom have?

The public gallery, now covered over, would have been very noisy during the 19th century, as trials were a popular form of entertainment.

The idea of bringing back the noise of a ‘chorus’ of people to the space, along with the isolated voices of the defendants, became very important to me.

- Stolen Things was commissioned by Ripon Museums and Arts and Heritage. It was funded by Arts Council England. Ripon Museum Trust has received funding from The National Lottery Heritage Fund.

- The artwork is now closed but you can listen to an excerpt on Paul's website.

Nightingale Café mural by Olivia Bouchard

Biggin Hill Memorial Museum, London

What was the idea behind your illustrations?

Olivia Bouchard: The Nightingale Cafe played a unique role during the Second World War. It was part of the military zone but nonetheless a place where pilots and soldiers from all horizons could grab a short instant of peace.

The Biggin Hill museum team wanted something a bit different from the imagery used within the museum.

What inspired you about Biggin Hill?

I spent a long time speaking with Geoff Greensmith, whose father ran the cafe during the war.

He was a very kind man who used to give free coffees to the German and Italian prisoners of war, the Italian prisoners being particularly keen on cappuccinos. I imagined how this taste of home could have been comforting for them at the time.

I love these kinds of hidden stories because they give a different perspective. It demonstrates that during this time of war, humans were capable of the worst but also, by these kind of gestures, of the best.

How do you think artists and heritage can work together?

I think artists and illustrators have an important place in heritage. It is not always easy, as it is a big responsibility to give a visual shape to people’s stories and memories, to the past.

At the same time, for me the role of an artist is not to make a documentary, it is to add another dimension.

At a time where museums and heritage sites are trying to reach larger and more diverse audiences, the place of artists is to be a bridge, telling stories in a universal language.

- Read more about our funding of Biggin Hill Memorial Museum.

- Find out more about Olivia's nomination for the World Illustration Awards.