Dear Mrs Pennyman

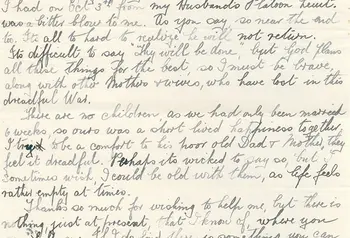

Bessie Walker from York had been married only six weeks when the platoon lieutenant wrote to say that her husband had been killed shortly before the end of the First World War. She wrote: ‘I try to be a comfort to his poor old Dad & Mother, they feel it dreadful. Perhaps its wicked to say so, but I sometimes wish I could be old with them, as life feels rather empty at times.’ Our new project, which has been funded by the Heritage Lottery Fund, aims to discover what happened to Bessie Walker and women like her in the years that followed.

The project is inspired by 120 letters discovered by volunteer archivists at Ormesby Hall in Middlesbrough. Mary Pennyman was the secretary of the King’s Own Scottish Borderers Widows and Orphans Fund and was just 26 years old when she began writing to the wives and mothers of men who were missing or killed during the First World War. The letters from across the UK and Ireland, which are now held in Teesside Archives, provide a window into the thoughts and feelings of women who would otherwise remain unnoticed by history, and this makes them very valuable.

Through their letters we encounter these women at a moment of profound sadness. Most try to manage their grief through recourse to religious beliefs and a sense of patriotic duty but occasionally fear, sorrow and even anger seep into their correspondence.

[quote]"Many First World War projects focus on the dead; this one focuses on those who had to live on."[/quote]

Pennyman’s role was to provide practical advice about pensions and recovery of personal effects. However she also asked the women about their lives and became a point of emotional support. One widow, Mary Smith from Sanquar, had to sell her house and take a position as a Lady’s maid. She wrote ‘… it is all too sad as we were so devoted to each other, I get about a great deal with my Lady and my mind is partly taken up with my work that really I shouldn’t grumble, I often think of those who are left worse off than I am’. By researching Mary’s story the project will bring greater understanding not just to the life of a Lady’s maid but also to the way in which women’s social and economic status were changed by war.

Pennyman herself is also an interesting figure. Her husband, a machine-gun officer, was declared missing during the war and this helped to bridge the class gap between her and the women who wrote asking for help. She tried to find ways to console them and wrote to one widow, ‘I am very glad to hear you have the children, they will make all the difference to you, for you will feel that you have something of your husband.’ Mary Pennyman died in childbirth at 35 and had no children.

Many First World War projects focus on the dead; this one focuses on those who had to live on.

Two student interns and a number of volunteers will help to research the lives of the women who wrote to Mary Pennyman and the project will tell their stories. Through the letters it will be possible to build a picture of the struggles and triumphs of women’s lives in the inter-war period.

The ‘Dear Mrs Pennyman’ project will share its work online. The letters will be digitized and a website is being constructed which will have a crowd-sourcing facility so that members of the public can get involved and contribute information. Public events will be organized to share the project’s findings and to learn from the experiences of volunteers.

The culmination of this work will be an exhibition to coincide with the centenary of the Armistice in 2018. This will provide a point of reflection on the impact of war on individual lives and on the fact that, for many, the ending of the war did not mean the end of sorrow. Ada Thornton from Sheffield wrote that she was not so anxious about the war ending now that her brother was dead, ‘You’ll understand this won’t you. We shall have no one coming home’.

You might also be interested in...